Africa – A Continent Divided by Borders but United by Blood

6 min read

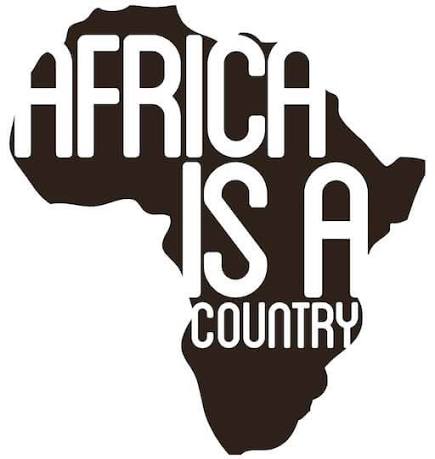

EDITORIAL – Africa is not a continent of 54 separate nations — it is one country temporarily divided by lines drawn by foreign hands.

The idea that Africa is a fragmented collection of states is a political illusion, one that was born out of greed and solidified by colonial conquest.

Long before the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, Africans lived, traded, married, worshipped, and traveled freely across the vast stretches of land that the world now calls “countries.”

The truth is simple and undeniable: Africa is a country — one people, one destiny, one home.

Before the colonizers arrived with their maps, guns, and flags, Africa was whole. Its people were united through trade, culture, kinship, and shared spirituality.

There were no artificial borders between Shona and Zulu, Yoruba and Ashanti, Berber and Tuareg.

The Nile connected the north to the heart of the continent, while the Sahara was not a barrier but a bridge — a highway of culture and commerce.

Empires like Mali, Ghana, Songhai, Great Zimbabwe, Mapungubwe, and Kongo thrived on systems of governance, education, and diplomacy that spanned thousands of kilometers. People identified by clan, tribe, and kingdom — not by foreign-imposed nationalities.

A man could walk from Timbuktu to Luanda or from Cairo to Cape Town and still find people who shared his customs, his gods, and his rhythm of life.

Africa’s unity was organic. It existed in the songs, languages, and trade routes that connected communities.

There was no “South Africa” or “Zambia” — there was simply Africa, a single land under the sun of creation.

The tragedy that fractured this unity began in Berlin in 1884, when European powers — Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, and others — gathered to divide Africa like a carcass on a colonial table.

Not a single African leader was present in that room. The conference, convened by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, was not about bringing civilization or Christianity as they claimed; it was about control, exploitation, and the carving of borders.

With a ruler and ink, they drew lines that had no meaning to the people who lived there — slicing through villages, families, kingdoms, and natural communities.

Rivers that once united were turned into boundaries. The Shona found themselves in Zimbabwe, Botswana and Mozambique; the Maasai were split between Kenya and Tanzania; the Ewe were divided between Ghana and Togo.

These borders were not African. They were European inventions, designed to weaken unity and ensure control.

The Berlin Conference gave birth to a divided Africa, where the people of one blood were told they belonged to different nations, with different flags, different languages, and different colonial masters.

Today, we say there are 54 African countries — but what do these borders really mean?

They are scars of colonialism, remnants of a design that sought to separate Africans from one another.

Our supposed “countries” share rivers, mountains, and histories. The borders may be written on maps, but they do not exist in the hearts of the people.

Africans across the continent share the same struggles, the same laughter, and the same dreams. Whether it is a farmer in Malawi, a miner in Zambia, or a student in Ghana, the challenges are the same — poverty, unemployment, underdevelopment, and the lingering shadow of colonial exploitation.

Our differences in language or accent are not barriers — they are variations of one African tongue.

Our cultures may vary, but they all celebrate family, community, and the rhythm of life.

When a drum beats in Senegal, it echoes in South Africa.

When one African nation celebrates freedom, the others feel the joy.

When one bleeds, the whole continent mourns.

So yes — Africa is one country, bound not by borders but by blood, history, and destiny.

The dream of a united Africa did not die with the colonial conquest. It found its voice again in the Pan-African movement — a struggle born from the hearts of African revolutionaries who refused to accept the artificial divisions imposed upon their motherland.

Leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, Patrice Lumumba, Haile Selassie, Jomo Kenyatta, and Robert Mugabe envisioned an Africa that would rise again as one people.

Nkrumah famously declared, “Africa must unite or perish.”

His vision was for a United States of Africa, where Africans would control their resources, trade freely, defend one another, and speak with one voice on the global stage.

Though the Organization of African Unity (OAU) was formed in 1963 and later became the African Union (AU), true unity remains incomplete.

The spirit of Pan-Africanism, however, continues to grow. Movements across the continent call for borderless cooperation, African-centered education, and economic integration through the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The new generation of Africans — connected by technology and a shared desire for dignity — sees the truth that politicians fear: the only real solution to Africa’s problems is African unity.

The modern African “nation-states” are still largely built on colonial foundations. Many use colonial languages — English, French, or Portuguese — as their official tongues, and their economies remain dependent on exporting raw materials to the very powers that once enslaved them.

But the real Africa is rising beneath these layers. It is the Africa of shared heritage, interlinked economies, and cultural pride.

It is the Africa where borders blur and cooperation grows — where regional blocs like SADC, ECOWAS, and the East African Community work to restore what Berlin destroyed.

When Africans trade among themselves, when they study each other’s histories, when they visit across borders freely, they are reclaiming their unity.

The continent is slowly awakening to the truth that it was always meant to be one — a single, powerful, self-reliant country.

Beyond politics and economics, there is something deeply spiritual about Africa’s oneness.

The ancestors who walked this land before the Berlin Conference knew no borders.

They worshipped the same Creator under different names — Mwari, Olodumare, Unkulunkulu, Nyame — but the essence was one, the belief in harmony between people, nature, and the divine.

That spiritual connection still binds the continent today. From the deserts of the Sahara to the valleys of the Zambezi, Africans share reverence for the land and respect for life.

The songs, dances, and rituals across the continent carry a shared rhythm — a heartbeat that refuses to be divided.

The time has come to erase the invisible fences of colonialism from our minds and hearts.

The future belongs to an Africa that sees itself not as 54 competitors but as one family. The continent’s power lies in its unity — in combining its 1.4 billion voices into one unstoppable force.

A borderless Africa is not a dream; it is a necessity. The continent’s progress depends on shared science, shared trade, shared defense, and shared purpose.

The African passport, already proposed by the African Union, is a step toward this reality — a symbol of freedom to move, work, and belong anywhere on the continent.

Africa was one before the colonizer came, and it remains one beneath the illusion of separation.

The borders drawn in Berlin were lines of division, but they could not break the bond of blood that unites Africans from Cape to Cairo, Dakar to Dar es Salaam.

To say “Africa is a country” is not a mistake — it is a statement of truth, a call to remembrance, and a declaration of destiny.

For when Africa finally rediscovers its unity, when the children of the Nile and the Limpopo stand together, the world will witness the rebirth of the greatest nation ever imagined — Africa, one country, one people, one destiny.