Documenting Heritage – Why Every Village Needs a Cultural Historian

6 min read

Feature – In every village, mountains whisper stories of forgotten wars, rivers carry memories of sacred rituals, and dusty footpaths recall the footsteps of ancestors who once walked with purpose.

Yet across the world, especially in Africa, rural communities are losing their cultural identity at an alarming rate.

Languages are falling silent, oral histories are being lost with the passing of elders, and traditional wisdom—once central to social cohesion and indigenous development—is slipping into oblivion.

In this digital age, where Western narratives dominate information spaces and globalisation continues to erode cultural uniqueness, one urgent solution emerges: every village needs a cultural historian.

These are not just archivists. They are custodians of collective memory, guardians of tradition, and torchbearers entrusted with preserving the soul of a people.

Across the African continent, development has often been mistakenly equated with abandoning tradition.

Modern houses replace mud huts, English replaces indigenous languages, and Western education sidelines local wisdom.

In the process, entire generations grow up disconnected from their roots.

The tragedy is that heritage does not disappear dramatically—it fades quietly.

It vanishes when an elder passes away without sharing the meaning of a clan totem. When a traditional rainmaking ceremony is dismissed as backward.

When youth migrate to cities and return unable to recite a single proverb from their community. When a village shrine is demolished to make way for a shopping centre.

These losses are not merely cultural. They strike at the foundation of identity and continuity.

Professor Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o once warned: “A people without memory are in danger of losing their soul.” Heritage is more than songs and artifacts—it is the foundation of belonging, the backbone of community values, and the compass for future generations.

Without a cultural historian in every village, that memory risks being erased forever.

A cultural historian is a person—young or old—entrusted with gathering, recording, preserving, and passing on a community’s cultural identity.

Unlike academic historians based in universities, village cultural historians live among the people. They breathe the air of the land they document. Their work is deeply personal.

They record Oral histories. Stories of origins, migrations, clan ancestries, local legends.

Cultural historians capture Languages and idioms. Dialects, proverbs, praise poetry, endangered vocabularies are all carefully captured.

Rituals and customs around Marriage practices, initiation ceremonies, traditional leadership are also preserved.

With the work of Cultural historians, Spiritual knowledge around Sacred sites, ancestral belief systems, taboos among others are packaged for posterity.

Material culture around Traditional crafts, tools, architecture, drums, and dress are also important and can be captured by Cultural Historians.

Music and dance around Traditional songs, instruments, war dances, storytelling rhythms are also preserved through efforts of these historians.

Indigenous knowledge systems in areas of ancient Herbal medicine, farming methods, conflict resolution are also preserved using such effort.

By doing so, they ensure that the story of the community is told by its rightful owners—not distorted or erased by outsiders.

Cultural historians help people answer one of life’s most fundamental questions: Who are we? Identity gives communities pride, resilience, and a sense of belonging.

A village without memory becomes vulnerable to cultural assimilation and exploitation.

Modern science has begun to recognize what rural healers and farmers have known for centuries: indigenous knowledge is a treasure.

From drought-resistant grains to medicinal trees, local knowledge holds solutions to global challenges. But without documentation, this wisdom will vanish.

Imagine schools teaching local history, literature, and heritage alongside mathematics and science. Cultural historians can help develop school materials that reflect local realities, making education relevant and empowering.

Shared heritage builds unity. When people understand their origins and respect their customs, conflicts rooted in ignorance and division decrease.

Village cultural historians help resolve disputes by reminding people of their shared past and kinship ties.

Heritage is wealth. Communities with documented history attract tourists, researchers, and investors. From museums to cultural festivals, traditional craft markets to heritage trails—cultural preservation can unlock new economic opportunities.

History has shown that when communities fail to tell their own stories, others will tell it for them—often with bias or misinformation.

Colonial historians once dismissed African societies as “people without history.” Why? Because we did not write. Now, in the era of digital storytelling, silence is no longer an option.

Preserving our heritage is not just about pride—it is about control. It is about self-definition. When foreign researchers record our culture without local involvement, they own the narrative, the intellectual property, and the financial benefits.

A cultural historian from the village ensures that knowledge remains where it belongs—with the people.

A village cultural historian does not need fancy equipment. They need passion, patience, and purpose.

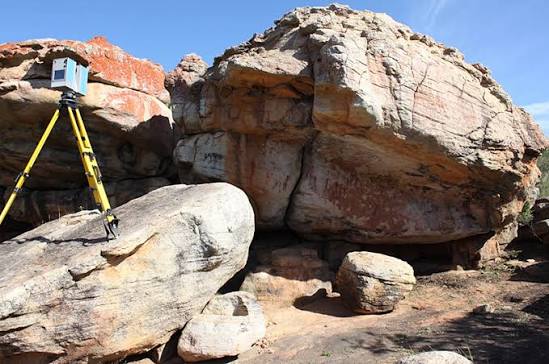

Their work includes Interviewing elders and recording oral stories, Documenting traditional sites using notebooks, cameras, or audio, Translating indigenous proverbs and idioms, Writing village history books or pamphlets, Archiving family trees and clan structures, Preserving traditional music and rituals, Collaborating with schools and cultural institutions, Creating digital archives using simple tools like smartphones among others.

Villages can even establish Heritage Committees to support the historian’s work, creating community archives stored in schools, chiefs’ courts, or local libraries.

Anyone can be a cultural historian. Age does not matter. Education level does not matter. What matters is commitment.

A primary school teacher, a village head, a passionate youth, a retired librarian, a traditional healer, or even a church leader can take on this role.

In many African communities, cultural preservation is often seen as the responsibility of elderly men, yet women hold an equally critical role.

Women are the keepers of family traditions, food culture, naming rituals, child-rearing wisdom, and marriage customs. No village cultural historian can succeed without women.

Likewise, the youth must be at the centre of this movement. Technology has given young people unprecedented power to record, archive, and broadcast.

The future of cultural heritage depends on them embracing their roots rather than running from them.

In Matobo, Zimbabwe, a young historian named Tawanda Ncube began documenting local rainmaking ceremonies, praise poetry, and clan histories after realizing that many rituals were being forgotten.

Working with village elders, he recorded more than 200 oral histories using only a smartphone.

Today, his work is used in local schools, and he has launched a community festival to celebrate Kalanga and Ndebele heritage.

His story is proof that cultural preservation is not a luxury—it is a calling. And one person can make a difference.

If heritage is not documented, it dies. If it dies, a people lose themselves. Every chief, every councillor, every school head, every village development committee must act now.

Let us appoint cultural historians in every village. Let us support them with recognition, resources, and respect. Create village heritage archives. Start intergenerational storytelling sessions. Record elders now—before it is too late. Include cultural education in schools. Use digital tools to preserve history. Celebrate identity with cultural festivals. Partner with universities and heritage organizations. Here we will never go wrong.

A village without history is a village without a future. Culture is not a relic—it is a living force that shapes how people think, work, love, and dream.

In our rush toward development, let us not leave behind the very essence of who we are. Development without identity is destruction dressed as progress.

Every village needs a cultural historian not simply to preserve the past—but to illuminate the future.

Let us document our stories. Let us own our heritage. Let us honour our ancestors by ensuring they are never forgotten.

Because when memory survives, a people survive.