The Sacred in the Soil – How Zimbabwe’s Landscapes Shape Our Identity

5 min read

Editorial – Zimbabwe’s story is not merely written in books or sung in oral traditions — it is etched in the very soil beneath our feet. The mountains, rivers, forests, and plains that stretch across our homeland are not just natural features; they are living archives of memory, identity, and spirit.

From the misty highlands of Nyanga to the roaring majesty of Victoria Falls, our landscapes are sacred, shaping who we are as a people and reminding us that culture, spirituality, and environment are inseparable.

Long before the arrival of colonial borders and Western cartography, the people of this land understood geography as genealogy.

Each hill, rock, and stream carried meaning — a name, a story, an ancestor’s breath.

To walk across Zimbabwe was to move through layers of history, myth, and lineage. The land was not owned; it was shared, respected, and venerated.

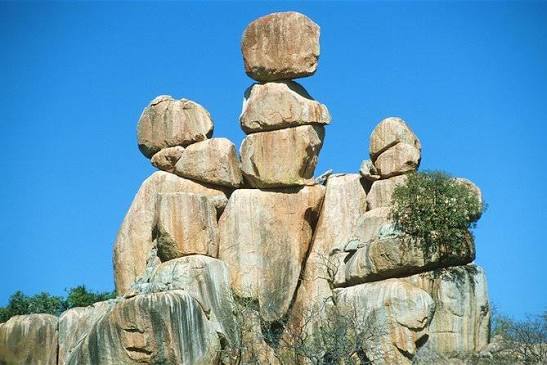

Take for instance the granite hills of Matobo. To the untrained eye, these might seem like mere geological formations. Yet to the Ndebele and Shona communities alike, they are imbued with sacredness.

It is said that the spirits of great leaders and ancestors rest within these rocks. Shrines like Njelele have for centuries drawn pilgrims seeking communion with the divine.

The Matobo Hills remind us that identity is not an abstract idea but a lived relationship with place — a recognition that our humanity is intertwined with the earth.

In African cosmology, the physical and spiritual worlds are deeply intertwined. The landscape is not separate from religion — it is religion. Sacred mountains, forests, and rivers are portals between the visible and invisible realms, places where the living meet the ancestral. This worldview resists the compartmentalization often found in Western thought, where land is viewed as property or resource.

In Zimbabwe, every sacred grove or hill tells a story. Nyanga’s rolling mist-covered peaks are believed to be the dwelling places of ancestral spirits, while the confluence of rivers often marks the site of ceremonies and offerings.

These natural spaces are sanctuaries where rituals affirm community bonds and ensure ecological balance. When droughts strike or illness spreads, elders turn not only to medicine but also to the land — performing ceremonies that reconnect humanity to the spiritual ecology that sustains all life.

Perhaps no place captures this union of spirit and landscape more powerfully than Great Zimbabwe itself. Rising from the granite plains of Masvingo, this ancient city is not merely a ruin — it is a statement of identity, ingenuity, and sacred design.

Built without mortar, the stone walls of Great Zimbabwe reflect not only architectural mastery but cosmological symbolism.

The conical tower, circular enclosures, and maze-like passageways align with patterns of social organization and spiritual hierarchy.

The builders understood that architecture must echo the rhythms of the earth. Great Zimbabwe is both a political center and a temple — a living testimony that African civilization emerged from spiritual harmony with the land, not its domination.

Yet, the sacred relationship between people and place was violently disrupted by colonialism.

Under European rule, sacred forests were cleared, ancestral graves desecrated, and communities forcibly relocated. The land was reduced to a commodity — a source of minerals, farmland, and economic exploitation.

This rupture severed more than just physical ties; it fractured identity. When people are alienated from their sacred geography, they lose part of their cultural compass.

The erasure of indigenous place names and the imposition of Western land tenure systems undermined traditional ecological knowledge and spiritual stewardship.

To heal as a nation, we must therefore restore not only ownership of land but also its meaning. Reclaiming our identity demands a re-sacralization of space — a return to seeing the soil as sacred, not simply as soil.

In today’s Zimbabwe, rapid urbanization, mining, and climate change threaten both the environment and the spiritual heritage embedded within it.

Sacred forests are shrinking, pollution poisons rivers once used for ritual purification, and tourism sometimes commodifies sites that once demanded reverence.

However, there is a growing movement — among traditional leaders, scholars, environmentalists, and cultural custodians — to restore respect for sacred landscapes.

Community-based conservation initiatives are reviving indigenous stewardship models, while cultural festivals reassert the significance of ancestral shrines.

At the same time, young Zimbabweans are rediscovering the spirituality of their environment through eco-tourism, storytelling, and heritage education.

Projects like the restoration of Matobo’s shrines and the preservation of Domboshava’s rock paintings show that modernity need not erase tradition.

Instead, it can build bridges between past and future — using technology and policy to protect spaces that sustain both biodiversity and belief.

Our national identity is not defined by abstract borders but by the sacred geography that binds us together.

The soil carries the bones of our ancestors, the songs of our foremothers, and the dreams of our children.

Every grain of sand in the Zambezi valley, every stone in the ruins of Khami, and every tree in the Bvumba forest is part of a larger story — a story of belonging, struggle, and spiritual endurance.

In a time when globalization threatens to flatten cultural distinctiveness, remembering the sacred in our soil is an act of resistance.

It reminds us that progress without reverence leads to ruin. Our landscapes teach us humility, patience, and continuity. They tell us that identity is not invented but inherited — cultivated through respect for what the earth reveals.

As Zimbabwe looks toward the future, the challenge is clear: how do we modernize without losing our soul?

The answer may lie beneath our feet. By protecting our sacred sites, reviving traditional ecological knowledge, and honoring the spirits that dwell in our mountains and rivers, we can build a development model rooted in reverence.

To walk upon this land is to tread on memory. To farm it, build upon it, and draw from it is to engage in a sacred covenant. Zimbabwe’s landscapes do more than sustain life — they give it meaning.

The sacred is not elsewhere; it is here, in the soil — shaping who we were, who we are, and who we are yet to become.